By Shlomo Goltz, from Smashing Magazine – http://bit.ly/1vkWFxC

In my experience as an interaction designer, I have come across many strategies and approaches to increase the quality and consistency of my work, but none more effective than the persona. Personas have been in use since the mid-’90s and since then have gained widespread awareness within the design community.

For every designer who uses personas, I have found even more who strongly oppose the technique. I once also viewed personas with disdain, seeing them as a silly distraction from the real work at hand — that is, until I witnessed them being used properly and to their full potential.

Once I understood why personas were valuable and how they could be put into action, I started using them in my own work, and then something interesting happened: My process became more efficient and fun, while the fruits of my labor became more impactful and useful to others. Never before had I seen such a boost in clarity, productivity and success in my own work. Personas will supercharge your work, too, and help you take your designs to the next level.

I hope that those who are unfamiliar with personas will read this series of articles, divided into two parts, and give them a try and that those who are opposed to their use will reconsider their position. Where the use of personas has generated uncertainty and even controversy, I have leaned in with curiosity and a critical eye, questioning the tenants of my discipline to determine what works for me — and I’m all the better for it. Perhaps what I’ve learned will help others in their journey to hone their work as well.

What Is A Persona?

A persona is a way to model, summarize and communicate research about people who have been observed or researched in some way. A persona is depicted as a specific person but is not a real individual; rather, it is synthesized from observations of many people. Each persona represents a significant portion of people in the real world and enables the designer to focus on a manageable and memorable cast of characters, instead of focusing on thousands of individuals. Personas aid designers to create different designs for different kinds of people and to design for a specific somebody, rather than a generic everybody.

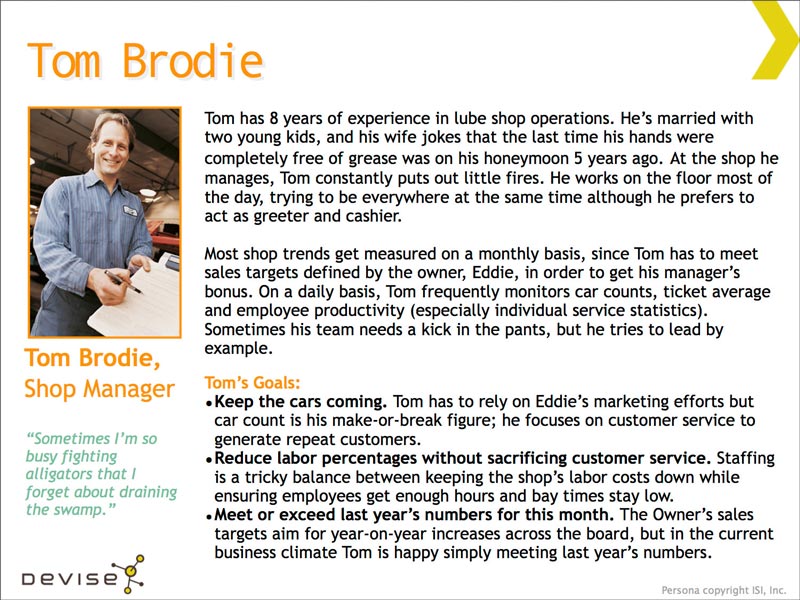

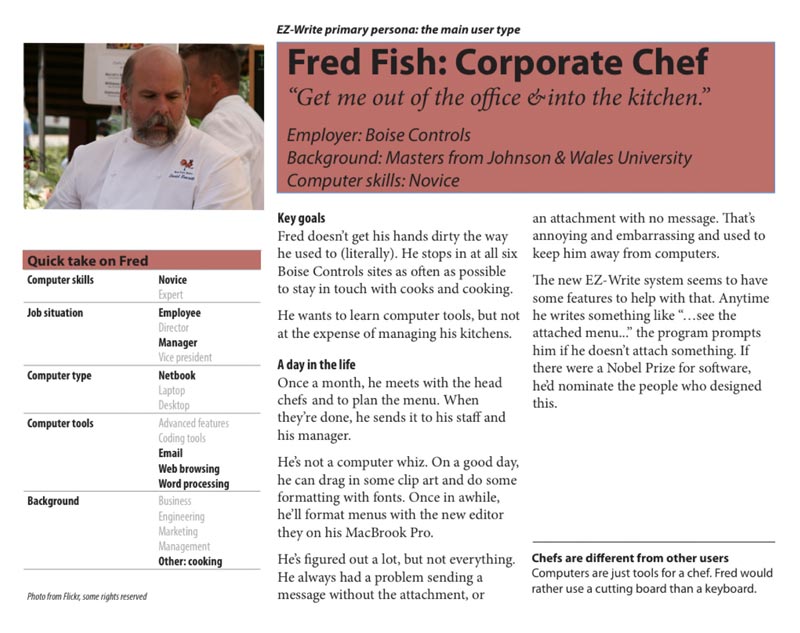

A persona document should clearly communicate and summarize research data. (Image: Elizabeth Bacon)

What Does A Persona Look Like?

While a persona is usually presented as a one-pager document, it is more than just a deliverable — it is a way to communicate and summarize research trends and patterns to others. This fundamental understanding of users is what’s important, not the document itself.

The main elements presented here are the key goals and the “Day in the Life,” which are common to all well-made persona documents. Other elements, such as the “Quick Take on Fred” are included because of team and/or project requirements. Each project will dictate a certain approach to producing persona documents. (Image: Interaction Design)

For designers looking for a jump start on creating persona documents, I highly recommend the persona poster template by Creative Companion. This poster organizes and formats all of the important information that a designer would need to create an amazing one-page deliverable.

Where Does The Concept Of Personas Come From?

Understanding the historical context and what personas meant to their progenitor will help us understand what personas can mean to us designers. Personas were informally developed by Alan Cooper in the early ’80s as a way to empathize with and internalize the mindset of people who would eventually use the software he was designing.

Alan Cooper interviewed several people among the intended audience of a project he was working on and got to know them so well that he pretended to be them as a way of brainstorming and evaluating ideas from their perspective. This method-acting technique allowed Cooper to put users front and center in the design process as he created software. As Cooper moved from creating software himself to consulting, he quickly discovered that, to be successful, he needed a way to help clients see the world from his perspective, which was informed directly by a sample set of intended users.

This need to inform and persuade clients led him to formalize personas into a concrete deliverable that communicates one’s user-centered knowledge to those who did not do the research themselves. The process of developing personas and the way in which they are used today have evolved since then, but the premise remains the same: Deeply understanding users is fundamental to creating exceptional software.

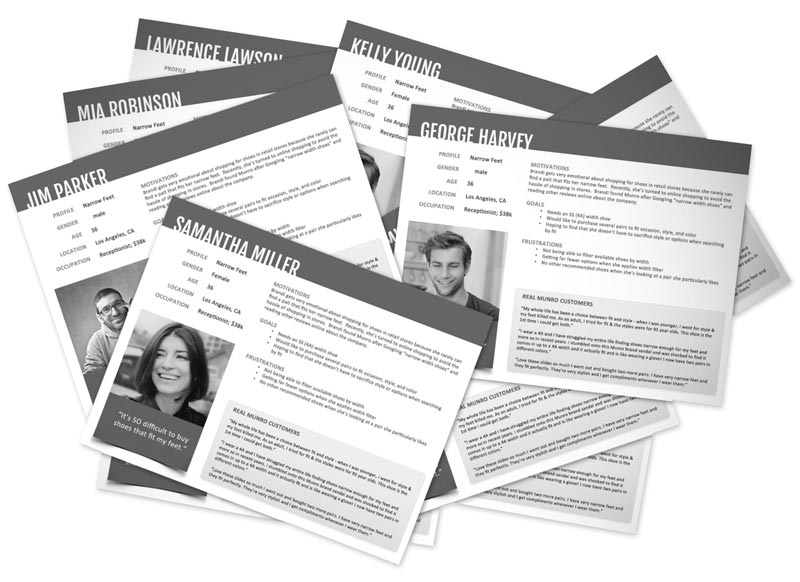

Personas are an essential part of goal-directed design. Each group of users researched is represented by a persona, which in turn is represented by a document. Several personas are not uncommon in a typical project. (Image: Gemma MacNaught)

How Do Personas Fit In The Design Process?

Since its humble origin, Alan Cooper’s design methodology has evolved into a subset of user-centered design, which he has branded goal-directed design. Goal-directed design combines new and old methodologies from ethnography, market research and strategic planning, among other fields, in a way to simultaneously address business needs, technological requirements (and limitations) and user goals. Personas are a core component of goal-directed design. I have found that understanding the fundamentals of this goal-directed approach to design first will help the designer understand and properly use personas.

In the summer of 2011, I was fortunate enough to become an intern at Cooper, which is where I learned (among other things) how to use personas. At Cooper, I found that, while personas are easy to understand conceptually, mastering their use with finesse and precision would take me many months. There, I witnessed everyone on the team (and even the clients) referring to personas by name in almost every discussion, critique and work session we had. Personas weren’t just created and then forgotten — they were living, breathing characters that permeated all that we did.

I learned that personas are an essential part of what constitutes the goal-directed process. I learned that personas, though important, are never used in isolation, but rather are implemented in conjunction with other processes, concepts and methods that support and augment their use.

Components of Goal-Directed Design That Support Personas

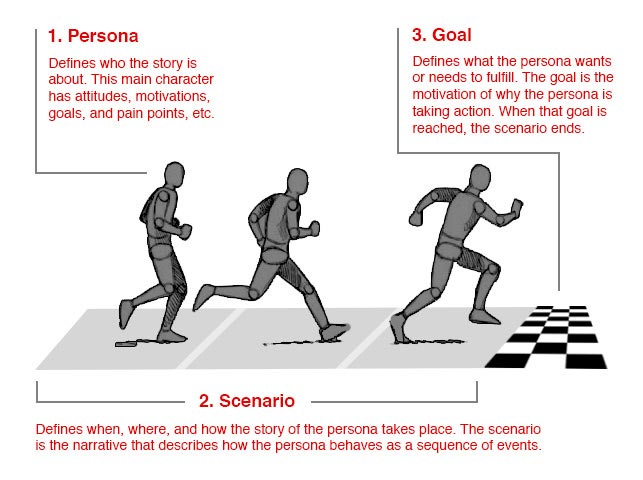

- End goal(s)

This is an objective that a persona wants or needs to fulfill by using software. The software would aid the persona to accomplish their end goal(s) by enabling them to accomplish their tasks via certain features. - Scenario(s)

This is a narrative that describes how a persona would interact with software in a particular context to achieve their end goal(s). Scenarios are written from the persona’s perspective, at a high level, and articulate use cases that will likely happen in the future.

The three parts of goal-directed design are most effective when used together. For instance, in order for a sprinter to reach their potential, they need a place to run and a finish line to cross. Without a scenario or end goal, the sprinter would have nothing to do or strive for.

Personas, end goals and scenarios relate to one another in the same way that the main character in a novel or movie goes on a journey to accomplish an objective. The classic “hero’s journey” narrative device and its accompanying constructs have been appropriated for the purpose of designing better software.

How Are Personas Created?

Personas can be created in a myriad of ways, but designers are recommended to follow this general formula:

- Interview and/or observe an adequate number of people.

- Find patterns in the interviewees’ responses and actions, and use those to group similar people together.

- Create archetypical models of those groups, based on the patterns found.

- Drawing from that understanding of users and the model of that understanding, create user-centered designs.

- Share those models with other team members and stakeholders.

Step-by-step instructions on how to create a persona is beyond the scope of this article, but we’ll cover this in the second article in this series.

What Are Personas Used For?

Personas can and should be used throughout the creative process, and they can be used by all members of the software development and design team and even by the entire company. Here are some of the uses they can be put to:

- Build empathy

When a designer creates a persona, they are crafting the lens through which they will see the world. With those glasses on, it is possible to gain a perspective similar to the user’s. From this vantage point, when a designer makes a decision, they do so having internalized the persona’s goals, needs and wants. - Develop focus

Personas help us to define who the software is being created for and who not to focus on. Having a clear target is important. For projects with more than one user type, a list of personas will help you to prioritize which users are more important than others. Simply defining who your users are makes it more apparent that you can’t design for everyone, or at least not for everyone at once — or else you risk designing for no one. This will help you to avoid the “elastic user,” which is one body that morphs as the designer’s perspective changes. - Communicate and form consensus

More often than not, designers work on multidisciplinary teams with people with vastly different expertise, knowledge, experience and perspectives. As a deliverable, the personas document helps to communicate research findings to people who were not able to be a part of the interviews with users. Establishing a medium for shared knowledge brings all members of a team on the same page. When all members share the same understanding of their users, then building consensus on important issues becomes that much easier as well. - Make and defend decisions

Just as personas help to prioritize who to design for, they also help to determine what to design for them. When you see the world from your user’s perspective, then determining what is useful and what is an edge case becomes a lot easier. When a design choice is brought into question, defending it based on real data and research on users (as represented by a persona) is the best way to show others the logical and user-focused reasoning behind the decision. - Measure effectiveness

Personas can be stand-in proxies for users when the budget or time does not allow for an iterative process. Various implementations of a design can be “tested” by pairing a persona with a scenario, similar to how we test designs with real users. If someone who is play-acting a persona cannot figure out how to use a feature or gets frustrated, then the users they represent will probably have a difficult time as well.

Are Personas Effective?

If you still aren’t convinced that personas are useful, you are not alone. Many prominent and outspoken members of the design community, including Steve Portigal and Jason Fried, feel that personas are not to be used. They make compelling arguments, but they all rule out the use of personas entirely, which I feel is much too strong. (A nuanced analysis of their anti-persona perspectives is beyond the scope of this article but is definitely worth further reading. Links to writings about these perspectives can be found in the “Additional Resources” section at the end of this article.)

Like any other tool in the designer’s belt, personas are extremely powerful in the right time and place, while other times are simply not warranted; the trick is knowing when to use which tool and then using it effectively.

Any tool can be used for good or evil, and personas are no different. If used improperly, as when personas are not based on research (with the exception of provisional personas, which are based on anecdotal, secondhand information or which are used as a precursor or supplement to firsthand research), or if made up of fluffy information that is not pertinent to the design problem at hand, or if based solely on market research (as opposed to ethnographic research), then personas will impart an inaccurate understanding of users and provide a false sense of security in the user-centered design process.

As far as I can tell, only two scientifically rigorous academic studies on the effectiveness of personas have been conducted: the first by Christopher N. Chapman in 2008, and the second by Frank Long in 2009. Though small, both concluded that using personas as part of the design process aided in producing higher-quality and more successful designs.

These studies join a growing body of peer-reviewed work that supports the use of personas, including studies by Kim Goodwin, Jeff Patton, David Hussman and even Donald Norman. The anecdotal evidence from these and many other writers has shown how personas can have a profoundly positive impact on the design process.

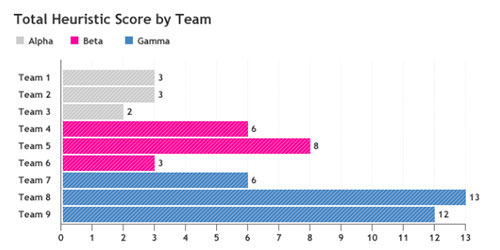

An excerpt from Frank Long’s study of the effectiveness of personas. Designs created by students who used personas and scenarios (pink and blue) scored higher than the designs of those who used neither (gray) in a type of usability test called a heuristic analysis.

How And Why Do Personas Work?

Personas are effective because they leverage and stimulate several innate human abilities:

- Narrative practice

This is the ability to create, share and hear stories. - Long-term memory

This is the ability to acquire and maintain memories of the past (wisdom) from our own life experiences, which can be brought to bear on problems that other people face. - Concrete thinking

This is the tendency for people to better relate to and remember tangible examples, rather than abstractions. - Theory of mind (folk psychology)

This is the ability to predict another person’s behavior by understanding their mental state. - Empathy

This is the ability to understand, relate to and even share the feelings of other specific people. - Experience-taking

This is the ability to have the “emotions, thoughts, beliefs and internal responses” of a fictional character when reading or watching a story.

Personas, goals and scenarios tap into our humanity because they anthropomorphize research findings. When hundreds or even thousands of users are represented by a persona, imagining what they would do is a lot easier than pouring over cold, hard, abstract data. By using personas, goals and personas together in what Cooper calls a “harmonious whole,” one is able to work in a more mindful way, keeping the user at the heart of everything one does.

If a designer truly understands and internalizes the user and their needs and how they could potentially fulfill those needs, then seeing potential solutions in the mind’s eye becomes much easier; rich and vivid ideas from the user’s perspective seem to percolate to the top of mind more rapidly and frequently. These ideas are more likely to turn into a successful design than by using other methods because the designer has adopted the user’s filter or frame as their own.

This potent combination of personas, goals and scenarios help the designer to avoid thinking in the abstract and to focus on how software could be used in an idealized yet more concrete and humanistic future.

Do I Really Need To Use Personas?

To determine whether personas would be appropriate, a designer must first step back and determine who they are designing for. Determining the audience for a design is deceptively simple, yet many people never think to take the time to explicitly figure this out.

The fundamental premise of user-centered design is that as knowledge of the user increases, so too does the likelihood of creating an effective design for them. If a designer designs for themselves, then they wouldn’t need to use personas because they are the user — they would simply create what they need or want.

Designers do design for themselves from time to time, but professionally most design for others. If they are doing it for others, then they could be designing for only two possible kinds of people: those who are like them and those who are not like them. If they are designing for people like them, then they could probably get away without personas, although personas might help. Usually, though, designers design for people unlike themselves, in which case getting to know as much as possible about the users by using personas is recommended.

Treat different people differently. Anything else is a compromise.

– Seth Godin

Personas help to prevent self-referential thinking, whereby a designer designs as if they are making the software only for themselves, when in fact the audience is quite unlike them. This is how most designers actually work: according to what they like or think is the right way to do things. Even a seasoned designer can go only so far on intuition. This is one of the biggest mistakes one can make when designing software (or anything else, for that matter).

Conclusion

As human beings, designers are all biased and can only see the world through their own eyes — however, they can keep that in mind when designing from now on. Designers must strive to the best of their ability to keep their biases and, dare I say, egos in check.

Designers don’t always know what is best — but sometimes users do and that is what personas are for: to stand up and represent real users, since real users can’t be there when the design process takes place. In your next project, there will come a time when you must decide what is in your user’s best interest. Just like in the movies, picture a devil and angel on your shoulders, where the devil tries to coax you to design something that pleases only your own sensibilities, and the angel is the persona who cries out in defence of their own needs. Who will you listen to?

Granted, not even the most disciplined user-centered and goal-directed designer can be completely unbiased. As professionals, we all use our best judgment to make decisions (based on knowledge of the field, knowledge of competitive markets and work experience), but some people’s perspective is more self-centered than others. Personas help to keep a designer honest and to become mindful of when they are truly designing for others and when they are just designing for themselves. If you are going to design for someone unlike yourself, then do your users a solid and use a persona.

We’ll discuss the process of creating personas from ethnographic research in part 2 of this series.